This week’s rebroadcast includes a post from 2007 and a downloadable PDF version of the key points (suitable for hanging up where you write).

Spend a few years as a screenwriter, and writing a scene becomes an almost unconscious process.

It’s like driving a car. Most of us don’t think about the ignition and the pedals and the turn signals — but we used to, back when we were learning. It used to flummox the hell out of us. Every intersection was unbelievably stressful, with worries of stalling the car and/or killing everyone on board.

It’s the same with writing a scene. The first few are brutal and clumsy. But once you’ve written (and rewritten) say, 500 scenes, the individual steps sort of vanish. But they’re still there, under the surface. It’s just that your instinct is making a lot of the decisions your conscious brain used to handle.

So here’s my attempt to introspect and describe what I’m doing that I’m not even aware I’m doing.

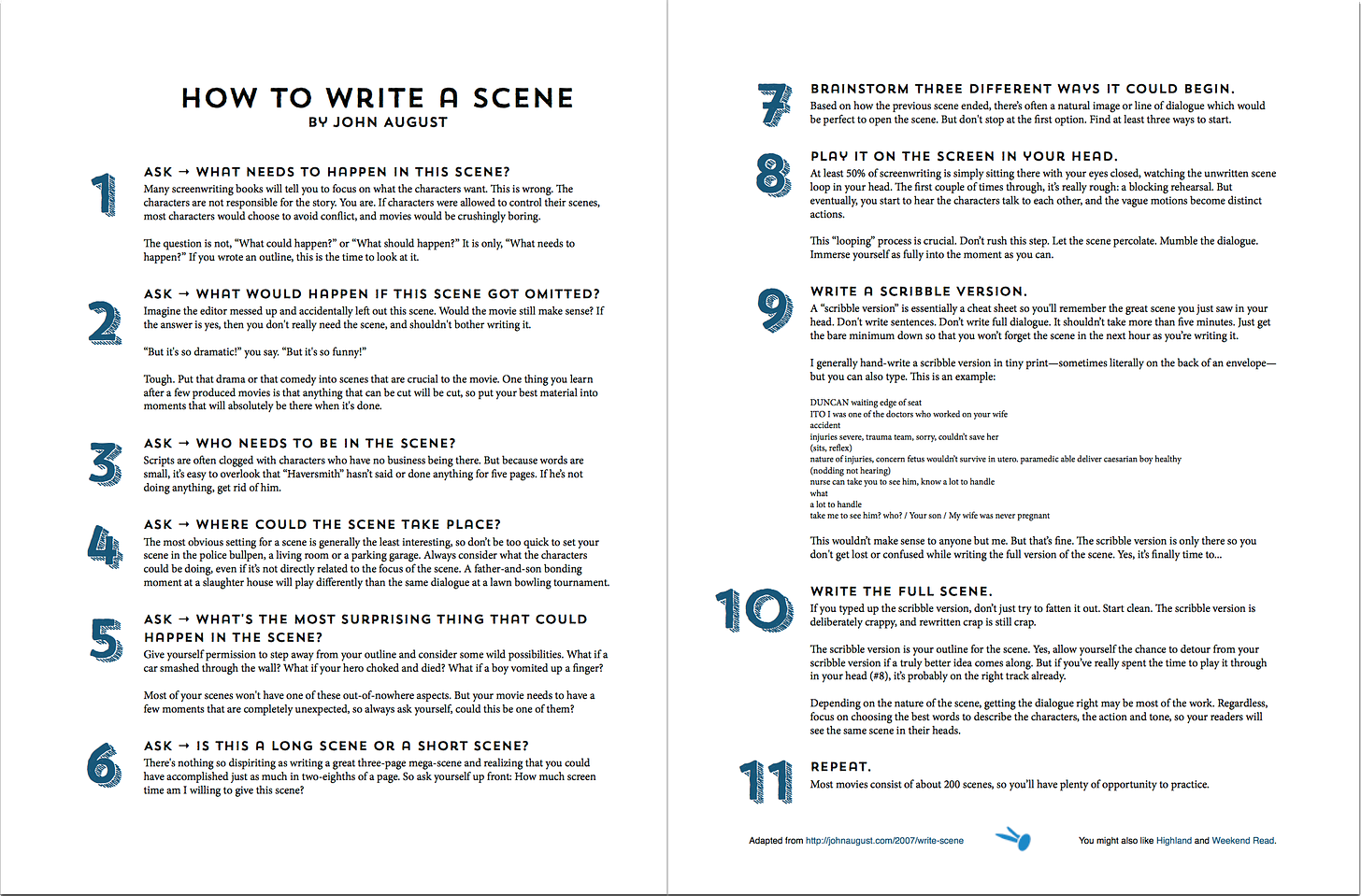

Here’s How to Write a Scene.

1. Ask: What needs to happen in this scene?

Many screenwriting books will tell you to focus on what the characters want. This is wrong.

The characters are not responsible for the story. You are. If characters were allowed to control their scenes, most characters would chose to avoid conflict, and movies would be crushingly boring.

The question is not, “What could happen?” or “What should happen?” It is only, “What needs to happen?”

If you wrote an outline, this is the time to look at it.1 If you didn’t, just come up one or two sentences that explain what absolutely must happen in the scene.

2. Ask: What’s the worst that would happen if this scene were omitted?

Imagine the projectionist screwed up and accidentally lopped off this scene. Would the movie still make sense? If the answer is “yes,” then you don’t really need the scene, and shouldn’t bother writing it.

But it’s so dramatic! you say. But it’s so funny!

Tough. Put that drama or that comedy into scenes that are crucial to the movie.2 One thing you learn after a few produced movies is that anything that can be cut will be cut, so put your best material into moments that will absolutely be there when it’s done.

3. Ask: Who needs to be in the scene?

Scripts are often clogged with characters who have no business being there. But because words are small, it’s easy to overlook that “Haversmith” hasn’t said or done anything for five pages. And sadly, sometimes that’s not realized until after filming.3

4. Ask: Where could the scene take place?

The most obvious setting for a scene is generally the least interesting, so don’t be too quick to set your scene in the police bullpen, a living room, or a parking garage.

Always consider what the characters could be doing, even if it’s not directly related to the focus of the scene. A father-and-son bonding moment at a slaughter house will play differently than the same dialogue at a lawn bowling tournament.

5. Ask: What’s the most surprising thing that could happen in the scene?

Give yourself permission to step away from your outline and consider some wild possibilities. What if a car smashed through the wall? What if your hero choked and died? What if a young boy vomited up a finger?

Most of your scenes won’t have one of these out-of-nowhere aspects. But your movie needs to have a few moments that are completely unexpected, so always ask yourself, could this be one of them?

6. Ask: Is this a long scene or a short scene?

There’s nothing so dispiriting as writing a great three-page mega-scene and realizing that you could have accomplished just as much in two-eighths of a page.4 So ask yourself up front: How much screen time am I willing to give to this scene?

7. Brainstorm three different ways it could begin.

The classic advice is to come into a scene as late as you possibly can. Of course, to do that, you really need to know how the previous scene ended. There’s often a natural momentum that suggests what first image or line of dialogue would be perfect to open the scene. But don’t stop at the first option. Find a couple, then…

8. Play it on the screen in your head.

At least 50% of screenwriting is simply sitting there with your eyes closed, watching the unwritten scene loop in your head.

The first couple of times through, it’s really rough: a blocking rehearsal. But eventually, you start to hear the characters talk to each other, and the vague motions become distinct actions. Don’t worry if you can’t always get the scene to play through to the end — you’re more likely to find the exit in the writing than in the imagining.

Don’t rush this step. Let the scene percolate. Mumble the dialogue. Immerse yourself as fully into the moment as you can.

9. Write a scribble version.

A “scribble version” is essentially a cheat sheet so you’ll remember the great scene you just saw in your head. Don’t write sentences; don’t write full dialogue. It shouldn’t take more than five minutes. Just get the bare minimum down so that you won’t forget the scene in the next hour as you’re writing it.

I generally hand-write a scribble version in tiny print — sometimes literally on the back of an envelope — but you can also type. This is what a scribble version consists of for me:

DUNCAN waiting edge of seat

ITO

I was one of the doctors who worked on your wife

accident

injuries severe, trauma team, sorry, couldn’t save her

(sits, reflex)

nature of injuries, concern fetus wouldn’t survive in utero. paramedic able deliver caesarian boy healthy

(nodding not hearing)

nurse can take you to see him, know a lot to handle

what

a lot to handle

take me to see him?

yes

see who?

your son. paramedic was able to

(grabs clipboard)

I know this may seem

My wife wasn’t pregnant

Your wife didn’t tell you…

My wife has never been pregnant. been trying three years. fertility clinic last week

I examined the baby myself. nearly at term.

I don’t know whose baby, not hers.

It’s kind of a mess, and really wouldn’t make sense to anyone but me — and only shortly after I wrote it. But that doesn’t matter. The scribble version is only there so you don’t get lost or confused while writing the full version of the scene. Yes, it’s finally time to…

10. Write the full scene.

If you typed up the scribble version, don’t just try to fatten it out. Start clean. The scribble version is deliberately crappy, and rewritten crap is still crap.

The scribble version is your outline for the scene. Yes, allow yourself the chance to detour from your scribble version if a truly better idea comes along. But if you’ve really spent the time to play it through in your head (#8), it’s probably on the right track already.

Depending on the nature of the scene, getting the dialogue right may be most of the work. Regardless, focus on choosing the best words to describe the characters, the action and tone, so your readers will see the same scene in their heads.

11. Repeat 200 times.

I’m neither pro nor anti-outline. They can be a useful way of figuring out how the pieces might fit together. They’re nearly essential in television, where many minds need to coordinate. But sticking too closely to an outline is dangerous. It’s like following Google Maps when it tells you to take Wilshire.

Do my own scripts hold up to this (admittedly harsh) standard? Yes, largely, but feel free to correct me where you disagree. Big Fish has quite a few meanders and detours, but that’s very much on-topic — it’s the reason the son is so frustrated.

As an example: Kal Penn in Superman Returns. He’s basically an extra.

Scenes are measured in eighths. You really do say two-eighths, not one-quarter.