🤨 What's the point, anyway?

Call it a premise, thesis, or assertion. It's the "why" of your story.

This week’s rebroadcast brings together a post from 2016 about finding the purpose for writing your story with a short excerpt from a draft chapter of the Scriptnotes book.

Michael Tabb takes a deep look at defining the premise of your story:

A premise is the core belief system of the script and lifeblood of the story. […] There can only be one premise per script from which all the ideas it contains serve, otherwise the script loses focus and its sense of purpose. Premise is hypothesis. It is the story’s purpose for existing at all.

For Tabb, premise is never explicitly stated. Rather, it’s the subtext for the piece as a whole.

It is not a word, theme, feeling, story, question, plot, or tone. It’s not about a person; it’s about the world in which we really live (even if your story is not set here). It is a strong statement with a point to make; it’s the theory the writer is trying to prove or disprove. This defines the author’s perspective.

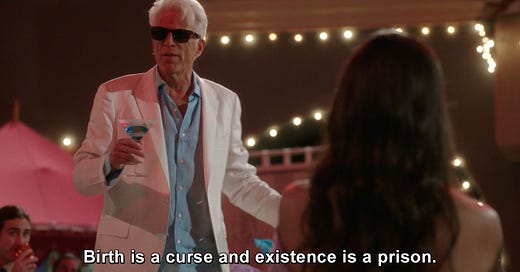

Basically, it’s your personal answer to the central dramatic question you’ve raised in the story:

Do souls live on after us? / Souls are eternal and reincarnated.

Can you ever escape your fate? / No, and it’s foolish to try.

Is trust granted or earned? / Trust is only earned.

I agree it’s worthwhile to distinguish between “what I’m trying to say” and “how I’m saying it.” But I think premise isn’t the best word here.

Tabb is using premise the way a philosopher would, where it means something like “the proposition that forms the basis for a theory.”

In Hollywood, premise commonly means “what the movie is about.” It’s a very short pitch, basically interchangeable with logline. The premise of Die Hard is that a cop has to stop a band of robbers by himself in an office tower. The premise of Armageddon is that an asteroid is headed towards Earth, and a team of misfits has to stop it.

One could argue that we’ve been using “premise” wrong. But we’re not going to suddenly start using it to mean something else. You’re likely to just confuse people by using “premise” a different way.

A better choice would be to pick a different term for what Tabb’s describing. Maybe “the point.” Or “thesis.” Or “assertion.”

Whatever you call it, I agree with Tabb that it’s best kept to yourself. Characters generally shouldn’t speak it in dialogue, nor should you discuss it with executives. Rather, let it be a touchstone that focuses your writing for this particular story. Work to expose it through scenes with characters in conflict.

Lastly, do you always know the answer to this question when you start writing? Not necessarily. Writing can be a process of discovery. It’s a Socratic dialogue with yourself. What matters is not knowing the point, but finding it.

Point of View

The writer needs a point of view because otherwise the story isn’t really about anything in particular. It doesn’t need to be text, it could be subtext. And it doesn’t have to be grand. It doesn’t have to be unsaid by anyone else before. But we do need a point of view.

What is the point, what are you actually wrestling with in the story? Even if characters aren’t speaking aloud, even if it’s not sort of obvious subtext, it’s the reason why you wrote the story, it’s the question you’re trying to answer.

We want to believe that the story is about more than just the surface plotting of it and that there’s a reason why you wrote this story. There’s a reason why the audience should be spending their time on it. That even if there’s not necessarily one answer, that you’re going to try to convince us of some point of view.

Craig: Scott Frank told me he wrote a script once and he sent it to, I won’t say who, but a big screenwriter, to get their opinion and that person’s response was, “This screenplay is well-written but it’s answering a question no one is asking.” And I thought that was a really tough love way of saying that whatever the point of view was there, it wasn’t something that would connect universally.

When you’re writing movies, you are creating the uncommon and the bizarre and the remarkable and notable because those are the stories worth seeing. But buried in there, something that is the opposite, incredibly common, completely universal, applicable to everyone’s life experience.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art, or Threads @ccsont@threads.net

The WGA Strike Continues — Get Involved!

We want to remind you of ways you can participate and support the effort to create a fair contract protecting the future of writing as a profession!

If you are interested and able, join a picket line and show your support. The Writers Guild also has a list of other ways to help.