This week’s rebroadcast brings together a few posts about structure, and reasons to consider that there’s not only one way to plan out a story.

I’m a 28-year old writer with a very old problem. I do my best work when I’m not consciously structuring a screenplay. I’ve found trying to shuffle scenes around on note cards about as useful as trying to construct a meaningful sentence out of syllables. So I’m reluctant to embrace a fully plotted mode of writing.

–Zackery

Structure isn’t really about tacking notecards on a wall. It’s about organizing ideas — sequences, scenes, and beats within those scenes — so that they can have the most possible impact. You don’t just create structure before you write. It happens inevitably with every character who walks in the door, or takes an action that spins the story in a different direction.

I doubt there are any working screenwriters who would say they’ve adopted a "fully plotted mode of writing." Whatever plan you’ve made for the movie, be it notecards, an outline or just an idea in your head, it’s always subject to change based on discoveries you make while you’re writing.

You’re beating yourself up over not plotting out your whole script beat-for-beat. Guess what? You don’t have to. For now, just write the best scenes you can, keeping in mind that they may need to be changed or cut to service the movie as a whole.

The best thing about fighting with yourself is that when you give up, you win.

When you write, are you consciously aware of structuring your screenplay, or it is something that is more instinctive?

— Brian

Galway, Ireland

When I was first starting out, I was paranoid about structure — but that’s because I didn’t know what it really was.

I had of course read Syd Field’s book, and I worried that if I wasn’t hitting my act breaks at exactly the right page number, I was a dismal failure. Then at USC I was introduced to a “clothesline” template, which was baffling. People smarter than me would talk about eight sequences, or eleven sequences, and I would nod as if I understood.

And now I do: It’s all bunk.

At the risk of introducing another screenwriting metaphor, I’ll say that structure is like your skeleton. It’s the framework on which you hang the meat of your story. If someone’s bones are in the wrong place, odds are he’ll have a hard time moving, and it won’t be comfortable. It’s the same with a screenplay. If the pieces aren’t put together right, the story won’t work as well as it could.

But here’s the thing: not every skeleton is the same.

Think about it in real-world terms. Human skeletons are pretty consistent, but you also have gazelles and giraffes, cockroaches and hummingbirds, each with a different structure, but all equally valid designs. The standard dogma about screenplay structure focuses on hitting certain moments at certain page numbers. But in my experience, these measurements hold true for Chinatown and nothing I’ve actually written.

My advice? Stop thinking about structure as something you impose upon your story. It’s an inherent part of it, like the setup to a joke. As you’re figuring out the story you want to tell, ask yourself a few questions:

What’s the next thing this character would realistically do?

What’s the most interesting thing this character could do?

Where do I want the story to go next?

Where do I want the story to end up eventually?

Does this scene stand up on its own merit, or is it just setting stuff up for later?

What are the later repercussions of this scene? How could I maximize them?

If you answer these questions at every turn, I guarantee you’ll have a terrifically structured screenplay. It might not hit predefined act breaks, but it will be consistently engaging, something that can’t be said for many “properly structured” scripts.

Roger Kamien’s description of the sonata form, a building block of the classical symphony, will seem familiar to screenwriters:

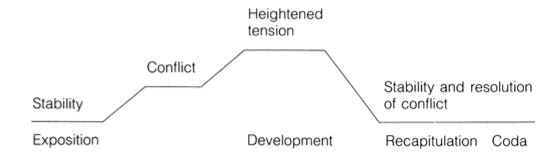

The amazing durability and vitality of sonata form result from its capacity for drama. The form moves from a stable situation toward conflict (in the exposition), to heightened tension (in the development), and then back to stability and resolution of conflict. The following illustration shows an outline:

This line of rising action is also the basis of modern screenplay structure.

No matter how you dress it up with templates and turning points, most movies work this way: you meet your players and themes, set them against each other, let things get rough, then find a new normal.

Sonata form is exceptionally flexible and subject to endless variation. It is not a rigid mold into which musical ideas are poured. Rather, it may be viewed as a set of principles that serve to shape and unify contrasts of theme and key.

With its long arcs and built-in act breaks, I’d argue that TV writing is even more symphonically-structured than features. Showrunners are our composers; Hollywood is our Vienna.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art, or Threads @ccsont@threads.net